Freiburg and London, 31 January 2023

Live Debate Transcript:

On 26 January 2023, German and UK experts discussed policy options for ending research waste in clinical trials in Germany, using the UK’s national #MakeItPublic strategy as a point of reference.

The online event was organized by TranspariMED, moderated by Cochrane Germany, and hosted by Consilium Scientific. Below is the transcript, slightly edited for clarity and brevity.

You can also watch a video of the event on YouTube.

TRANSCRIPT

Till Bruckner, TranspariMED [00:00:01]

Hello, everyone. Thank you very much for joining us today. My name is Till Bruckner, from Consilium Scientific’s TranspariMED campaign. We're going to be talking about whether and how the UK clinical trial transparency system can be implemented in other countries.

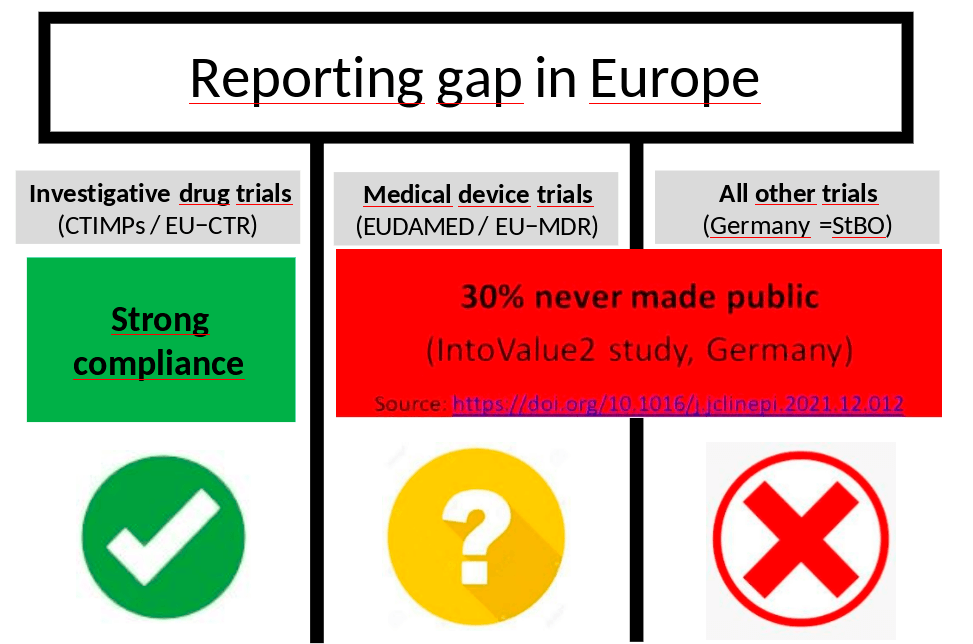

That discussion is really relevant to the whole of Europe because in Europe right now we've got three different regulatory systems for clinical trials which have got a great influence on transparency.

- First, best of all, we've got the system for investigative drug trials [CTIMPs] where now it's a legal requirement to make the results public. And there's also effective enforcement by regulators. And I think especially the German regulators have distinguished themselves by taking this seriously.

- The second one is for medical device trials, where there's also a legal requirement coming in to make the results [of some device trials] public. But I think if we're looking forward at what enforcement and compliance is going to look like, I think that's going to be a really big challenge.

- And then finally, we've got all other trials. So there's trials that are neither investigative drug trials nor the particular medical device trials covered under the medical device regulation and in Germany and in all other major EU countries. Right now, there is absolutely no legal requirement to make the results of those trials public. And of course, there's no enforcement either because there are no rules to enforce.

Sources: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00103−022−03631 −x

https://www.transparimed.org/single−post/clinical−trial−regulation−europe

So when we look forward for the investigative drug trials, I think we can expect very strong compliance in the years ahead. For the medical device trials and all “other” trials, it's going to be difficult. We've got Daniel Strech on the panel today who led the IntoValue2 study, which found that around 30% of those types of clinical trials run by academia in Germany will never make their results public. So there's a huge amount of research waste happening in that area.

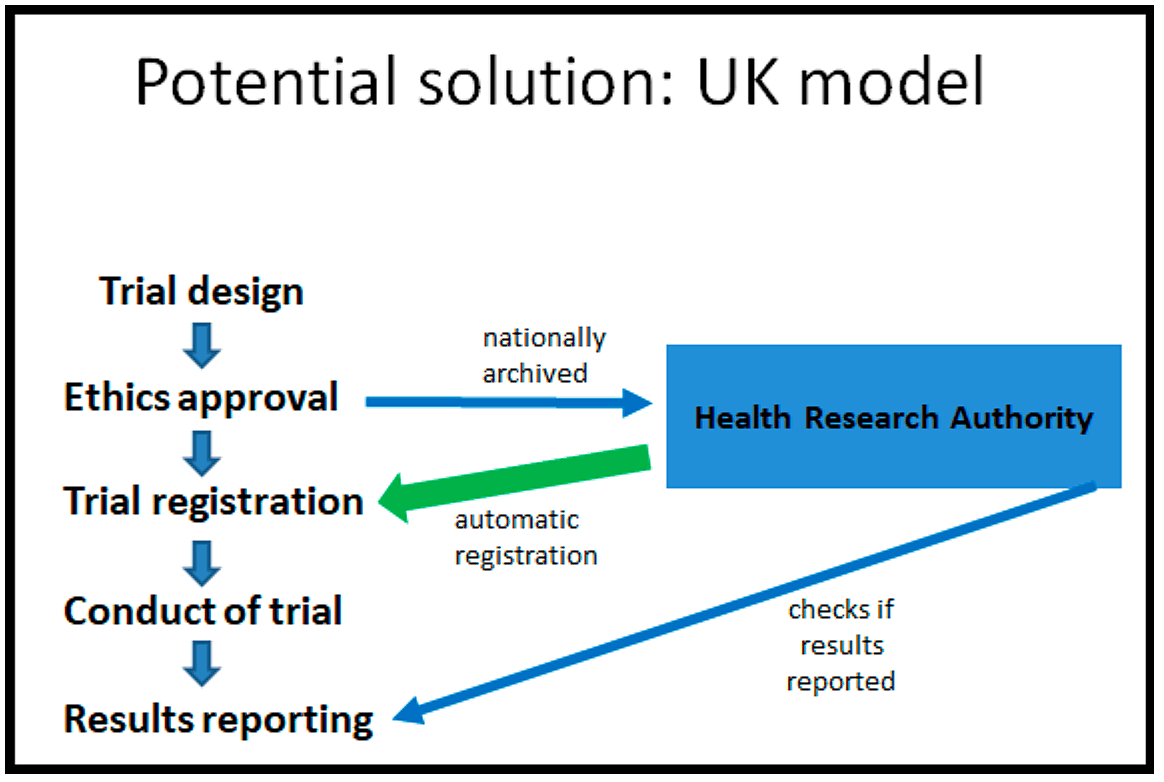

And in that context, the UK model I think is a really interesting potential solution to this problem that could be adopted elsewhere in Europe. How does it work? On the left you can see the flow of a normal clinical trial where the trial gets designed, then it gets submitted for ethics approval, it gets registered, then you run the trial and finally at the end you make the results public. So the UK model goes with this flow.

But the new system they're putting into place now is that following ethics approval, the ethics approval documentation gets archived nationally by the Health Research Authority. Somebody in the Health Research Authority then registers the clinical trial for you based on the ethics documentation.

Then you go on, you run the trial as you normally would. You make the results public. And afterwards, the Health Research Authority does double checks. Have you made the results public? And if you haven't made the results public, they will contact you and they will remind you to please make the results public.

So it's a very simple system and it's got some big advantages.

- The first one is, of course, you can see it at the bottom, make information public. It covers all clinical trials. It moves beyond these artificial regulatory distinctions because every clinical trial needs ethics approval and it makes sure that 100% of those are registered and 100% of them also make their results public. It means it's really a watertight system covering all trials.

- The second advantage is making transparency the norm. So there are very, very clear rules that cover all clinical trials. So trialists are very clear about what's expected from them. And there are very efficient processes that automatically steer people towards transparency.

- The third advantage is making transparency easy, and that means less bureaucracy for medical researchers, less paperwork for medical researchers, to allow scientists to focus on what they do best, which is science.

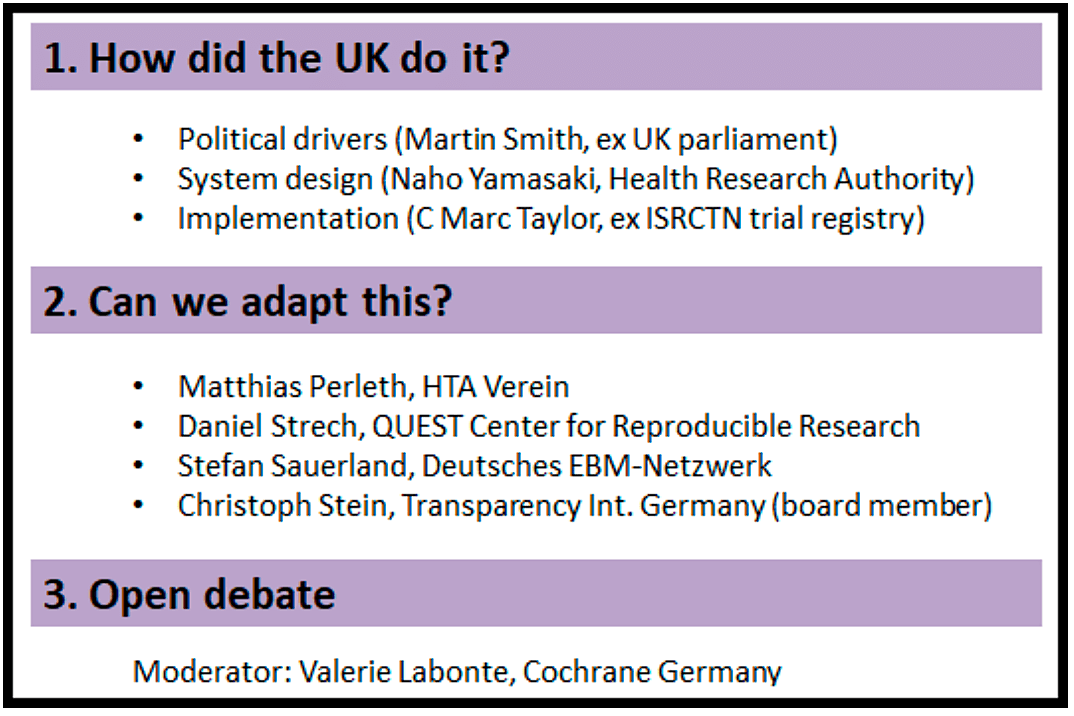

So can this be done elsewhere? And that is the topic of the meeting today. We got a great panel together.

- First, we'll hear about how the UK managed to put this system into place so well. We've got Martin Smith, who used to be with the parliamentary committee that developed this plan, talking about the political drivers behind the system. Then we've got Naho Yamasaki, who works with the Health Research Authority; she led the design of the system. And finally, we've got C. Mark Taylor, who used to be the chair of the ISRCTN trial registry, and he will be talking about the sort of practical problems of implementing this.

- Second, we will have comments from Germany. We've got Matthias Perleth from the G-BA, Daniel Strech from the QUEST Center for Reproducible Research, Stefan Sauerland from the German EBM network, and Christoph Stein, who is a board member of Transparency International Germany. And they'll each just very briefly discuss what the opportunities and the barriers are for using this system in the German context.

- After that we've got one hour of free discussion and that will be moderated by Valerie Labonte from Cochrane Germany.

Martin Smith, ex UK House of Commons

Back in 2018, I was a member of staff supporting the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee in the UK Parliament. Now, that's a formal committee of the UK Parliament. It's a cross-party group, MPs appointed by the House specifically to scrutinize the work of the UK Government when it comes to science and technology issues. I think there is an analog in the German Bundestag committee system, but in the UK select committees don't focus on reviewing legislation. The focus is strictly on government scrutiny and what they do is they produce reports and the government is required to produce a written response to those.

We would say that they're very influential rather than powerful. Specifically, they don't hold executive power, but they do hold a lot of political sway. So back in 2018, the committee was holding an inquiry into research integrity in quite a broad sense. But then as a result of that, it published a dedicated report specifically on clinical trials transparency. I was a member of staff for both of those pieces of work, which

involved analyzing the written submissions, liaising with the experts in these areas and drafting the report for the committee to consider. Since then, I've moved on. I now work for the Wellcome Trust in London, so I'm very much speaking here in a personal capacity, drawing on my own reflections from that time.

But I'll start my, if I may, with a quote from the committee's 2018 report: “Clinical trials transparency is as much a question of political will as it is a technical issue”. And I think that captures the UK's journey here and is it is a good framing for the comments I want to make.

The first point I want to make is that actually it was campaigners that created the opportunity for scrutiny in this area. They were the ones that directly prompted the committee to focus on this specifically. The Commission's initial inquiry was on research integrity, things like fraud and error and publication bias, these sorts of things. There was actually a small number of submissions to that inquiry, including from Till and AllTrials and several others that made the point that actually clinical trials transparency is a much bigger issue than any of these things, or at least have much more frequently occurring problems than an issue such as fraud, much as they may be very high profile and problematic.

But when I was originally scoping the research integrity inquiry, I hadn't included transparency as a particular area. And so it was in response to those submissions that the creating the opportunity that campaigners such as Till saw to try and get some political emphasis on this that led to the committee's work.

I should also say that this wasn't actually the first time the committee had looked at trials transparency. Its predecessor five years before in 2015 (note: actually it was in 2013), although with a different group of Members of Parliament, of course, with that political turnover. They had also looked at this and it produced some very damning conclusions, but they hadn't really been acted on properly. Again, spotting this was an extra advantage for the committee coming back to this, the ability to follow up on previous work, particularly where something's been ignored, is quite appetizing for a committee.

But one of the differences between 2013 and coming back to it in 2018 was the establishment of the Health Research Authority in 2014, I think, and you'll hear from the Health Research Authority later. But what struck the committee was that it was part of the HRA’s responsibilities to promote research integrity. But what the committee saw from the submissions and the public evidence sessions that it held was that the HRA didn't seem to have a strategy to do this. If anything, it seemed to be taking a passive approach to promoting transparency rather than driving improvements, and it wasn't measuring its performance based on the change that it was creating.

I think that's significant because the existence of the HRA that created an obvious owner for this problem until it was sketched out how they fit into the system now, which works very nicely. Another piece of the puzzle was that actually there's been a tremendous proliferation of rules and regulations requiring registration and reporting agendas. Till has touched on it in the German context. But in the UK these were very much not being enforced.

So the legislative and the regulatory framework was already there. Now those two things combine in an interesting way. In this case, I think having spent a number of years working with Members of Parliament, I say there's a couple of things that really attract their attention. One is the scope for calling out strongly something that is fundamentally explainable in a clear, really clear way. The second is the scope for them doing that, actually creating a change as a result. Both of those things are attractive, being on the right side of history, but also being able to actually make a difference. Fundamentally, whatever your cynicism when it comes to politicians, maybe the vast majority are in this business in order to create change.

And so for clinical trials transparency, this seemed like a fixable problem, a clear: right now the legislative framework is better, but what was needed was the political will to really push it over the edge.

I think the other thing to mention is that at the time, the committee could see that some of the responses from the HRA seemed like fairly weak excuses. The position didn't seem very defensible when it was pointed to the fact that there wasn't a budget to do these things. Attempts to try and assess what kind of money we're talking about suggested that it wasn't actually that expensive in the grand scheme of things, particularly given the scope and the importance of this issue. I think the committee’s chair in particular could smell the scope for really laying into this and following up regularly if the HRA wasn't interested in following up on the committee's recommendations by simply saying that it wasn't needed at all.

And actually, my part of the story ends with the committee's report, with its recommendations and then the government's response. And so probably the central recommendation that the committee made was that the government should ask the Health Research Authority to develop a new strategy to really drive forward improvement on clinical trials, transparency, and if needed, to supply it with the regulatory powers of the budget to really make a difference in this area.

Delighted to say that the government very much accepted that quote, and the HRA's response to this was exactly the right one. And I'll finish up my comments with a quote from the HRA chair at the time, which was: “While promoting research, transparency has always been a key part of our work. The committee has set us a challenge to move away from merely encouraging best practice and instead to drive improvements. We accept that challenge.” That is music to a committee.

This was definitely the right thing to do and a huge amount has happened since 2018 as a result of the HRA rising to that challenge. I think the committee was ready to push a lot further if it needed to, but it didn't need to. So congratulations very much to the campaigners who got this onto the committee's agenda in the first place, and then the HRA for responding so well.

Naho Yamasaki, UK Health Research Authority (HRA) [00:14:08]

I'll follow on the story from where Martin left off. Before just following the thread of Martin's talk, I just want to give a little bit of a background about the Health Research Authority. For those of you who are not familiar with us, we were created 11 years ago now to streamline and coordinate health and social care research across the UK. We're an arm's length body of the Department of Health and Social Care, so the government has devolved all of its responsibility to us in that regulation arena. Most of our function applied to research undertaken in England, but we worked closely with the Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to provide a UK wide system and the key components to the work that we carry out.

As far as the research approval process is concerned, we provide a UK wide coordinated service for research ethics review. We support the 60 research ethics committees. We also undertake assessment on behalf of the National Health Service or whether the proposed study in England and Wales complies with legal and governance requirements. And we also support a committee that reviews studies wishing to use identifiable patient data without consent. So those are the kind of functions that the operational support that we provide.

And as Martin mentioned, we also have a statutory responsibility to promote research transparency. Following on from the committee's report and the challenge that we were given about developing the strategy, we set about going ahead with this, recognizing that at the time available data showed that, really, transparency performance in the UK was quite poor.

Only about 70% of the clinical trials were registered on a recognized registry, even though it was a condition of the Research Ethics Committee approval. Also, 75% of clinical trials of medicine didn't report results to the [EudraCT] registry on time, the rates for other studies being lower. And despite that sort of proposal in the [ethics] applications, the majority of clinical trials didn't inform participants about the results.

In order to address this, we really went about setting the strategy. And what we did first was to establish an advisory group to develop a draft strategy, and that looked at the four pillars of transparency. So those are registration, publication of results, communicating results back to participants, and also sharing of research data and tissue.

We set about consulting on that strategy. And this is an important component of trying to get the buy-in of the sector and the community, because what we wanted to put in the strategy was something that is ambitious, that takes us to the vision of full transparency across the system, but through means that are meaningful and manageable and that have the buy-in of the entire sector.

So we went through a three month public consultation period, June to September, and we also had an online survey set up at the same time as going through a series of public workshops. We also conducted a number of webinars for our Research Ethics Committee members, held a number of focus groups with patients, and I think this is quite important as well. We had quite a number of workshops with our staff because we recognize that as well as having sector support, we need the staff to enable that change to happen.

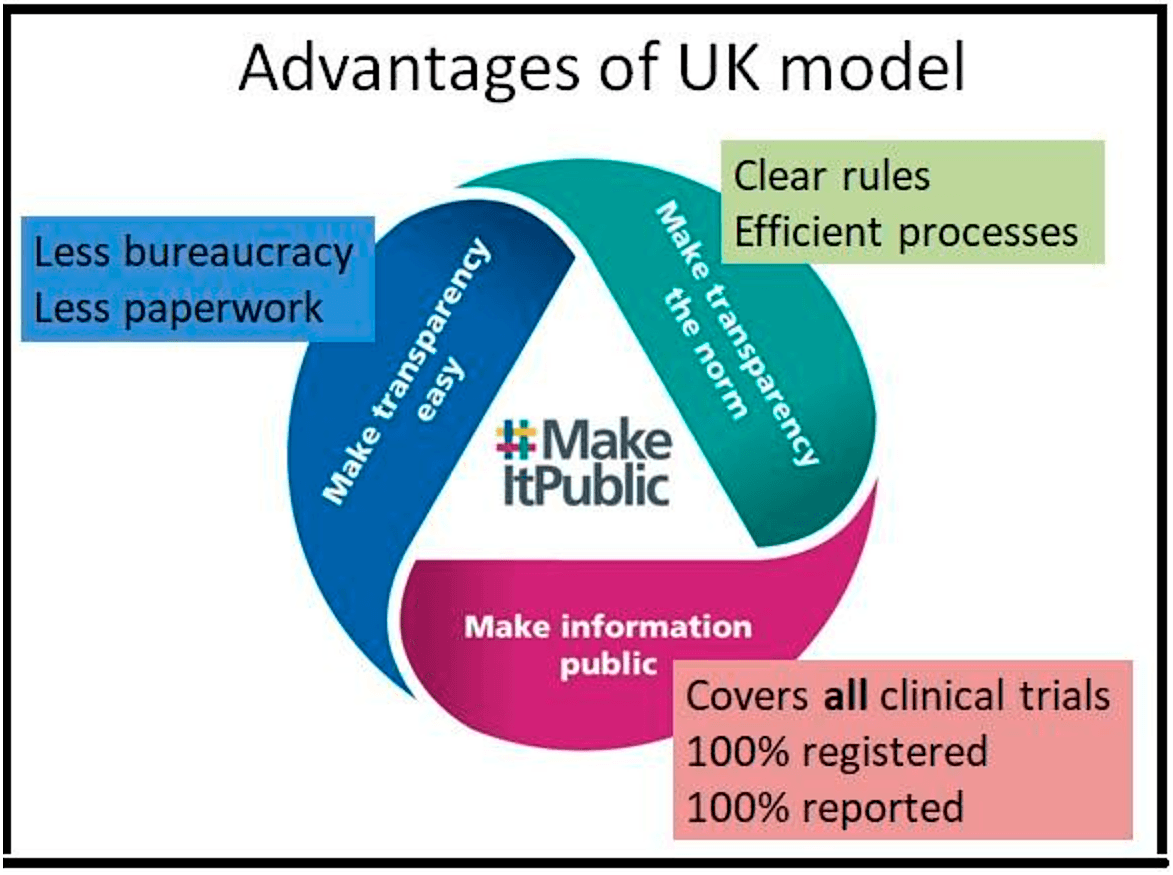

Through the online survey, we received just over 700 individual and organizational responses to the questions that we posed in relation to the draft strategy. So we digested all those responses and came up with the data, what we called the #MakeItPublic strategy, which was published in July 2020.

The vision we articulated is quite simple. It's that trusted information about health and social care research is publicly made available for the benefit of all. And in order to meet that vision, we made ten commitments within the strategy sitting on the three overarching goals: that we will make transparency easy, make transparency the norm and make information public. And I think this was underpinned by a knowledge that the research community, through this dialogue that we had and the consultation process, that they wanted to be open and transparent about their research. And so broadly there is, you know, big support for transparency.

But we also recognize that there are many things that make transparency hard to do, and that's why we wanted to provide a combination of approach through the strategy, including a system of process changes, provision of learning guidance, and also highlighting good and poor practice, and through those multiple approaches aimed to make meeting research transparency requirements just part of what we all do.

I just want to talk about a couple of things that we did in terms of making it easy and the norm during the consultation.

- Researchers told us that transparency requirements aren't always clear, so that is that the easy strand? To a large extent. So one of the first things we did was to clarify requirements. We reviewed and updated our guidance on our websites and application forms and approval letters. So, you know, our expectations are made much clearer for the researchers and sponsors.

- We also developed a roadmap. It showed an end to end of a clinical trial with key points at which applicants need to fulfill research transparency requirement so that they can plan in advance. And that is a prototype roadmap that we want to develop further.

- We also produced a learning module that explains how to write a plain language summary of research findings, and we're thinking about other types of guidance in the area.

So those are the changes to try and support, making it easier for researchers to understand what they need to do, when they need to do it, and how they can do transparency well.

And in terms of making transparency the norm in the strategy, what we said was that we will reward and celebrate good practice and highlight poor performance also, that we will work with other players in the system, key stakeholders, funders, other regulators and publishers to make sure that our expectations of our research transparency are consistent and aligned. And it's fair to say that there is a lot more that we need to do in this area. But that is our ambition – and also that we will take action if people are not fulfilling their transparency requirements. So, you know, a combination of nudging and probably a little bit more a stronger ways of taking action to make change happen.

So in terms of celebrating success and highlighting good practice, we had a conference and published our first annual report in November of 2021 and a recording that is available if people are interested. We also established a campaign group which brings together key stakeholders from across the system to try and galvanize change, stakeholders that have been instrumental in shaping some of these conferences and the report and that the supporting the design of three workshops that we are planning to run in March this year.

And the idea is that we continue working with the campaign group as well as the wider stakeholder community to continue our work on aligning expectations and, you know, really got to keep that drumbeat going about the importance of research transparency.

And the other area that we are looking at is, as I said, on taking action and thinking about what is the best way to, you know, as a regulator to manage [when] expectations are not met. And for us to take any kind of action, we need to rely on having proper performance data. And at the moment, we don't have a full set of information that we can act on.

And we've been putting systems into place to enable us to do that. So. In September 2021, we introduced a new way of submitting study final reports. It's always been a requirement that all studies submit a final report to a research ethics committee 12 months from the end of the study. But until then we didn't have a standard form or specify exactly what must be included in this report. So in order to amend that, we produced a standard set of data that people need to submit to us through this final report informing us of how they met or whether and how they met research transparency requirements. That's in relation to registration, publication results and feeding participants and sharing research data and tissue.

So there's four pillars of transparency I talked about. We also asked a summary of results to be submitted as part of the final report, and we started to publish these on our website to accompany the lay summary of the study plans that we get as part of the application process.

And we also started a partnership with a UK registry called ISRCTN, to talk about registering clinical trials on behalf of sponsors. We're starting this with clinical trials of medicines [CTIMPs] and we are planning to expand that further in the future. The idea is to take the burden away from sponsors because we'll supply that that data to the registry. But also that's another way of making sure that there is 100% coverage in the future.

So that's the work that we've done and we continue to do. And I think it's fair to say that there is more work to do. But there is definitely the will and the commitment from the organization to really about this practice across the system.

C. Mark Taylor, Ex chair of the ISRCTN trial registry [00:25:05]

I have been for the last ten years the chair of the company that owns the ISRCTN [clinical trials] registry. It's a slightly unusual arrangement. It was decided early in its early days that it wouldn't be part of a public body and that it would be best to run it independently under the ownership of the company running through a contract.

Before I became the chair of this company on my retirement, I was an official in the UK Department of Health and Social Care, and I worked for the Chief Medical Officer and the Director of Research and Development for ten years on building up the structures which include the Health Research Authority. I remember writing the policy documents that led to its creation.

The particular themes that I that I'd like to go into in the moment really follow on from what Martin and Naho were saying. I don't want to say this by way of discouragement to anyone in Germany, but a lot of the elements that Martin described actually date from a long way back and certainly back to early in my time at the Department of Health. So joint working between the Research Ethics Committee system and the MHRA [UK medicines regulator] approval service that predated the Health Research Authority. And there was a powerful interest in giving someone the responsibility for promoting transparency.

And that's what led to the act that set up the Health Research Authority in 2014, giving it a duty to promote transparency in the public interest. I think the HRA is only public body in the UK that has a duty like that, despite all the other areas of research. And when the transparency strategy was published in 2010, it was happening alongside the testing of a combined improved approval process which linked the activities of the Ethics Committee system to the regulation of medicines and devices. And as Naho was saying, it broadened the remit not just to the licensed medicines and devices, but to any sorts of research that were happening in the public interest and could get past an ethics committee. So that was the context for focusing on clinical trials.

And it wasn't just the Health Research Authority and the MHRA. I mean, since the early 2000s, our Chief Medical Officers have been campaigning in the World Health Assembly to promote transparency, along with the registration of trials and reporting. And that drive up was because of the need they sought to coordinate the scientific response to pandemics and to threats to global public health. So this is has been as much of an international concern, I'd say, of a solidarity with other people who are interested in transparent science around the world as it is about the responsibility of the Health Research Authority in England to respond to the, as I thought, justified criticisms of our parliamentarians.

So when the ISRCTN registry started its work as it was, it started as an international registry back in 2000 with strong support behind the scenes from the British government by the Chief Medical Officer and the expectation that it would engage with others in the W.H.O. system.

So this is it. You've asked me to talk about implementation, but my point is that the implementation of the strategy which we're seeing now started long before. The importance of the strategy is that it really does a good job of drawing things together. And as Martin and Naho said of giving the HRA the remit to show leadership in this area, and it definitely has shown leadership outside the field of regulation because alongside the international companies, active and licensed products, there's a large sector in the UK with charities promoting health science. You may be familiar with our Association of Medical Research Charities, 150 members with over a billion a year, which not long ago set up an open research platform to encourage the sharing of results. When Naho's preparations for the chart of the strategy were underway there was already a set of charities that had signed a joint declaration in 2017 at the World Health Organization about aligning policies around the publication of [trial] results.

And so the Transparency Forum that the HRA set up was a very receptive place in which the ISRCTN registry could publicize some of the data behind the failures that Martins saw highlighted in parliament. ISRCTN, as a background to the strategy, was publicizing the data around the situation, not only in the UK but in other research active countries. And I have to say we were comparing ourselves very actively with the performance of the German universities and regulators, and actually is a miserable performance of the French ones. It was of particular concern to me that French universities in particular were awful at making sure that the results of their clinical trials came into the public light.

So there was public trust and making things easier for researchers, and the work of the registry alongside combining the review processes. [The system has been] for quite a long period about being customer focused and you're hiring a stable expert team to advise people doing their rather difficult task of registering studies. I say difficult because at that stage, not many sponsors were taking much interest in it. So offering detailed advice and giving features to the registry that gave into registration, updating and reporting, and also sending out reminders to people who had failed to meet deadlines. Those were really important things for a registry to do, not just curating the data.

And there's a lot more to do internationally on aligning data sets and data flows. That's one of the things that I think is a big unfinished business, and I'm delighted that the HRA, as well as the National Institute for Health Research in the UK, is taking interest in the end to end data flow, which makes it easy for people to move the description of their work in and out of the various concerned systems.

I mean, the business of registration and reporting ought to be a side effect of properly run data management and management systems in sponsors, and those ought to be aligned with the regulators, and we're some way off from that.

So you asked me to do a few lessons learned, and I won't spend very much longer on this, but there's a lot to think about here.

First of all, I've been emphasizing that it took a long time to change the culture, and we're not there yet. But the big change comes when sponsors are insisting on transparency and setting up internal systems and employing research managers to help their research as to how to deal with the challenge of remembering through the whole life of a research activity what they ought to be doing about transparency.

And the second thing is the supporting cast. It takes a long time to set up a network of research managers. And the Research Integrity Office in the UK [UKRIO] has been promoting debate about transparency alongside the HRA for over ten years. And Martin's referred earlier on to the main thrust initially of the inquiry, which all parliamentarians took up. But many institutions in the UK still offer very weak, inconsistent support to their research management and for their research teams. They don't support people who are capable of knowing from one end of an activity to another what they're missing, and updates and reporting elements.

And then the final thing is the research data systems, because they haven't really caught up with policy in practice yet. And that's a mistake that I think we made. So I think we made a mistake when we were introducing the partnership between the HRA and the ISRCTN. Before launching that, we should have spent much longer talking to data managers in industry and the universities and funders about the mechanics of lifting data easily from one system to another, and aligning the processes and the definitions, which would mean that you don't have to have a new discussion about the registration dataset.

Just to say as a researcher, I own that dataset. It's a correct description in the registry of what I'm planning to report on when the research is completed. Because the sting in the tail of this, and this is my final point, is that in the UK we still have many researchers who insist that they want to go on registering with ClinicalTrials.gov because that's what they're used to doing in France. Everybody registers with ClinicalTrials.gov if they do. And I'm a tremendous admirer of the US National Library of Medicine, but it's really not the business of the NLM to run a registration and reporting service for the whole of the developed world, including everybody here who's completely capable of doing the job properly for themselves.

And we know from experience that if you register with the wrong registry and don't follow up, that's the best way to ensure under-reporting or poor quality reporting, low engagement from sponsors and really poor relations with the people who participated in the trial. So it means research that's wasted from the point of view of participants of wider society. It's lots of faith breaking faced with the people who have a real interest in the results of our clinical research.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane (moderator) [00:38:23]

Valerie Labonte here from Cochrane Germany. And now we'll hear from the German experts on how a clinical trial transparency system could be implemented in Germany. So questions are what adjustments would need to be made to adopt the system to the German context and what is likely to be the main challenge and how could that be overcome? I would ask Matthias Perleth to respond first, please.

Matthias Perleth, HTA Verein [00:38:58]

Hi everybody and thank you very much for the for setting up this meeting. I’m the Chairman of the Society for Health Technology Assessment. That's only a very small society, so we probably are not capable of organizing the whole process in Germany. But of course, we can do everything to we can in order to somehow support the activities in Germany.

It's not easy to answer to these two questions. Just let me give you some short remarks on that. As we can see in the example of cars that obstruct the German roads, we know in Germany every detail about these cars. So registration and transparency obviously is possible. However, in health care, there is less transparency and this probably has very different reasons.

One good example that transparency is possible and that mandatory registration could become a reality is a trauma and implant registry. In about 2025, it will become effective for hip and knee implants. They have to be registered mandatorily from 2025 on. And this development is significant in that the mandatory registry in Germany could become reality. But of course, as has just been said, this requires some sort of a development and control change since this registry is already set up since about ten years ago, but only on a voluntary basis.

But the German ministry has taken up this development also in response of the situation with medical devices and Europe in general and scandals with faulty devices in order to improve the security situation in Germany. So that was the catalyzing factor for setting up a mandatory registry. What we could do, is we could try to support a campaign in Germany. I think what we would need is a national alliance.

And I'm very happy, for example, that also in this meeting is a representative of the German network for evidence based medicine [DnEBM]. We would need probably ethics committees as they also play a crucial role in the UK system. We would need people from the German Parliament, members of Parliament, from the Ministry of Health, from research, funders and sponsors, and from medical universities. I think many of the trials that never get published are probably investigator initiated trials.

However, what makes it more difficult, is that we do not have a German health research authority or an equivalent of that. So we would need to find other ways in order to put this national alliance together and somehow bring this to the attention of our politicians. As Martin said at the beginning, it will be a matter of political will. And, well, we as a smaller society can try to support this process.

Daniel Strech, QUEST [00:43:23]

There certainly would be a lot of technical adjustments necessary if we would in Germany want to copy something like the process that you are about to install and have already partly implemented in the UK. And I will not comment on all of these more technical aspects, but from a higher level perspective, the more conceptual and policy adjustments.

I would say that all European countries are close in the procedure for drug trials [CTIMPs] because all approvals for drug trials from the ethics committees go to the authorities that are bound to have the clinical trial registered in the European clinical trial registry. So we have this registration process in a certain way already established, but only for the drug trials. And they only reflect about maybe one third of all interventional trials.

The policy adjustment would have to be that German research ethics committees that not only approve drug trials, but all other interventional trials too, they need to have a process for informing a centralized body about the approved trials. And we don't have this yet. As Matthias mentioned, we don't have an HRA, so we would need to see what this centralized body could be.

Now there are several bodies that obviously would play a role, but we don't have this centralized body that takes the leadership that, as you mentioned, is important now. We have this umbrella organization for all German ethics committees [AKEK].

And plus, I mean, this was only the registration part to get all trials registered. Then second, results reporting, which is relatively easy maybe for drug trials or according to the legal requirements. But again, all non-drug trials, we would need really a change in policy in Germany for having this guaranteed.

With regard to main challenges, I would say one challenge could be if we do not make use of all the existing resources that we have. I think in many ways we will not need to reinvent, not only because there is already one real example from the UK, but also from the resources that we have in Germany.

We have these different parties and bodies that I just mentioned that in principle would have the ability to oversee all the different trials and they could in principle implement some procedures for forwarding information, centralizing this and makes it public.

But beside organizations, I would say it's also very important to make use of all the software and code that allow us to get information from registries and about results reporting in a more automated way. So it's not necessary that people are really manually checking for registration results. A lot of software that already exists allows us to get information from the German registry of clinical trials [DRKS], from ClinicalTrials.gov, from the European clinical trial registries [EudraCT & CTIS]. And it's important that the organizations in Germany make use of this already existing software to make everything as easy as possible as you stressed out them as being an important part of your initiative.

Last but not least, the challenge is to get the relevant decision makers together. So I would say to people sitting here together today from Cochrane or the EBM network, the joint Federal Committee that matters [G-BA] is also represented a little bit. They are different parties. Also my [QUEST] Institute for Responsible Research. I think there would be people that are happy to build an alliance in supporting maybe also pushing a little bit.

But we need the decision maker alliances also to take leadership. And I hope that this would be one important event today to kick this off a little bit. Thank you.

Stefan Sauerland, German EBM Network (DnEBM) [00:49:03]

Thank you for organizing this meeting. The German body I'm heading, the Non-Drug Department [of IQWIG], are experiencing all these problems. For example, we had a report where it was difficult to arrive at a conclusion because we had so many registered trials that had not produced any results. But I'm also here for the German network for evidence-based medicine. And I've worked many years at the university, so I know also the other side because I did many clinical trials and registered about a dozen surgical trials, some of which are well reported and some of which are not so well reported.

I agree with what has been said so far. The main problem is that we have these different types of trials as Till has already categorized them.

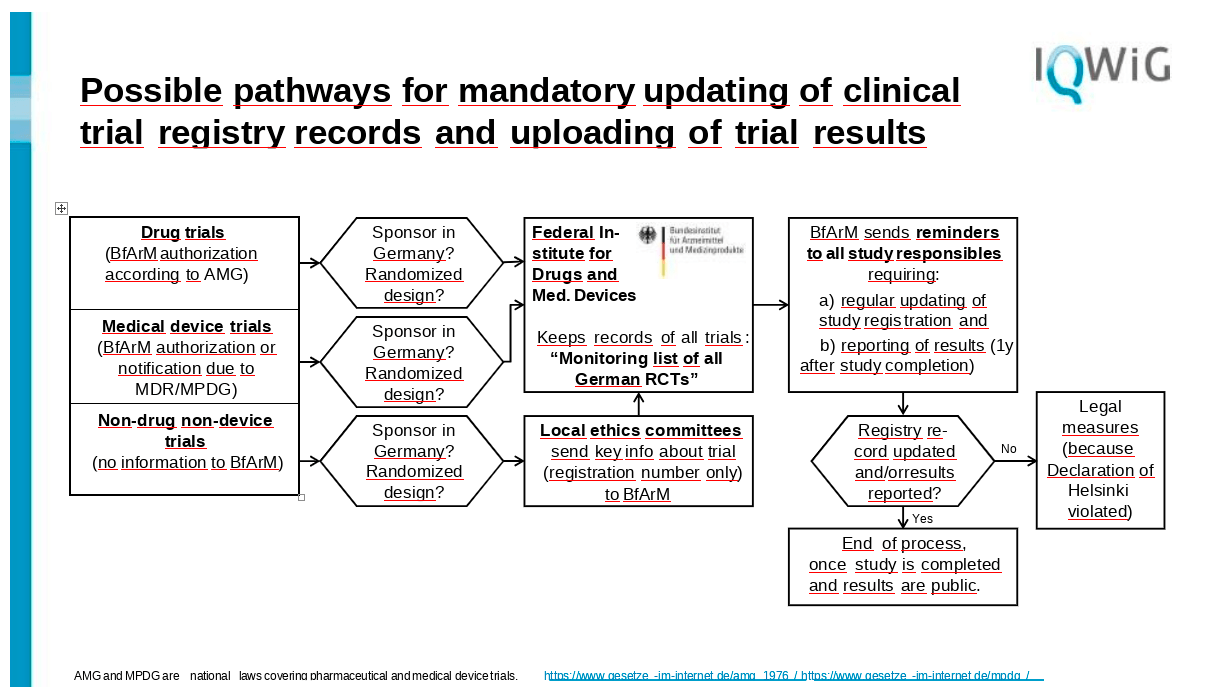

We have the drug trials and these are all reported not only to the ethics committees in Germany, but have to be authorized by the Federal Institute of Drugs and Medical Devices [BfArM] who also run the German register of clinical trials [DRKS]. They know about trials that fall under the [European] medical device regulation or the German counterpart.

But the main problem are other non-drug, non-device trials because these are only seen by the Ethics Committee and they are quite poor in convincing the investigators to report the results.

So I think the main role here in the replacement of the British Health Research Authority would be BfArM, because they already have all these trials on drugs, they have many of the trials on devices. And if we could convince the local ethics committees that they send all their trials that fall in the third category to BfArM, BfArM could keep a record of all trials. And this would then create such a thing like a monitoring list of all German assets. So they would know of all trials that have at least a randomized design. We can talk about nonrandomized studies that have been registered too. But for the start I would begin with only the randomized controlled ones.

And of course this is only necessary if the sponsor is in Germany because the other trials, if there's just a German center participating in the trial, I think the whole issue must be settled in the country where the primary sponsor is located and now comes the heavy part.

BfArM would be required to send out reminders to all responsible, and they would at least require updating the study registration once a year. And of course, if the study has reached the end of the recruitment period one year ago, would require reporting of results in any way.

In my view, BfArM is quite well-suited for this purpose because they also have this authoritative role in German research and they would not go unnoticed, to put it frankly. So the investigators then of course either they can follow the updating request of BfArM, and in the end the results get reported.

But if this is not the case, and this is the most critical point, then there would have to have some legal measures at hand to press investigators first. Of course they could contact the investigators’ bosses, let's say the dean of the university, or they could contact the ethics committee that had once agreed to the trial so that the investigator cannot start any new trial before finishing the previous trial in a correct way.

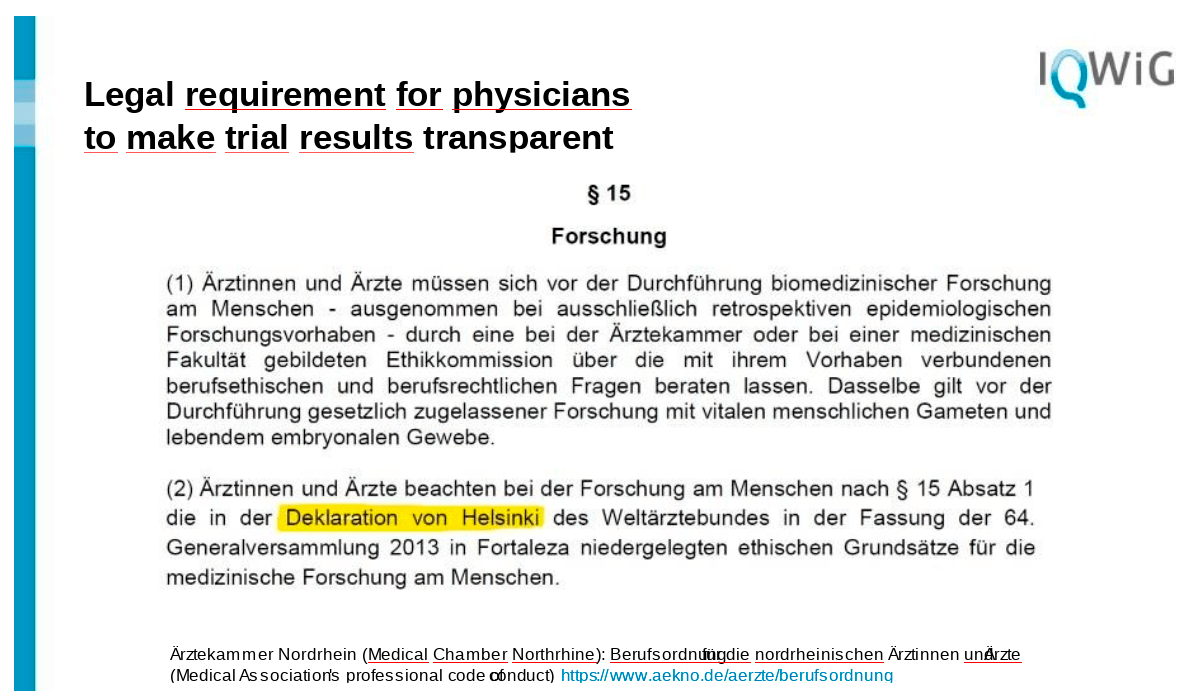

And the most serious element would be that they could contact the physicians chamber to request that the physicians conducting the trial follow the Declaration of Helsinki. Everything is already in the law in a way because in Germany at least, there is a legal requirement in the medical chambers statutes for my area that we all have to follow the Declaration of Helsinki. And this means we have to publish the results of clinical studies.

And therefore there is some possible legal basis that could give an argument to contact the investigators. So the main problem would be that we need some resources, maybe at the ethics committees, but mainly at BfArM. The technical issues that Daniel just mentioned, automatic recording or automatic connection between the records and publications and so on, would not require a legal change. It would just require that some official at the Ministry of Health is, well, issuing a directive so that BfArM takes over this role in the in the German healthcare sector for keeping trial registry records updated and making trial results available. That's it.

Christoph Stein, Transparency International Germany board member [00:56:19]

Since all my previous predecessors have already talked about the current situation, and I think it's been described very well, I only have a few questions. First of all, I'm not quite sure why I am sitting here. Why is Germany the target of this panel today and not the EU? Why is Ursula von der Leyen not sitting here? I think my experience, and I am more or less speaking as a as a clinical researcher, is that we usually try to observe the laws and we we are very receptive to laws in Germany and we are mostly receptive to the EU laws. So I think we should, in my opinion, instead of targeting Germany as the only country here, we should target the entire EU.

But then I have a few questions to my colleagues from the UK. First of all, I'm not exactly sure what they mean by publication. We have talked a lot about publications within the last several years in the context of this pandemic, and we have seen that there is a huge problem with publications. We have to talk about whether people just read preprints or peer reviewed publications. And so for us, I think that needs to be clearly defined.

And another very detailed questions to my colleagues from the UK: what is your experience with the number of trials? Obviously, registration and all these requirements pose a burden on people conducting trials, including the sponsors. And my question is, did you ever see a decrease in the number of trials due to this additional burden?

That's really all I have to say at this point.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane Germany (moderator) [00:59:05]

Thank you very much for your initial responses. Now we can start the discussion. Everyone from the audience, of course, is welcome to type questions or comments, and I will try to read at least some of them. I hand over to Mark Taylor, who raised his hand.

Marc Taylor, ISRCTN [00:59:21]

I raised my hand only in order to answer those two questions.

So first of all, about what we mean by publication. There is a policy amongst trial registries, which comes from the World Health Organization. And in fact I've been involved in some activity to clarify exactly what's required on declaring results at one year after the conclusion of the trial, so that by this summer, the World Health Organization will provide further details of what's wanted. And that's particularly important when there is no general publication of those results. That's the point one.

Point two, have we seen a reduction in the number of studies? Absolutely. The pandemic had an enormous impact on research in the UK, partly because the people providing facilities in the NHS had to prioritize in order to relieve the pressure on our health services and the aftereffect is to produce a major reduction in the number of clinical trials in cancer in particular. So it's a big issue both how many trials run and whether they are productive. And I really don't think that the the business of having to register your trial and declare your results is the major obstacle to getting trials done and producing a useful outcome..

Nano Yamasaki, HRA [01:01:24]

So on the point of publication as well, just going back to those two questions. In the final report that we ask people to submit to us, we do ask a couple of questions. One of the questions is, has the registry been updated to include a summary of results? So that's a very specific component about surfacing. And we also ask whether the applicant has followed that dissemination plan that was submitted to us as part of the application, and that could be about publication in an academic journal or a sort of open access journal.

So we don't necessarily stipulate exactly, you know, sort of what publication have you done. That's just clarifying the kind of the questions that we ask of researchers and sponsors.

In terms of the impact of this transparency requirement on the number trials happening in the UK, I would echo Mark's point that I think is very difficult to really put a cause and effect on those. And I would say largely if we see any kind of forward in the number of trials happening in the UK, it will be for much wider factors and not necessarily those linked to requirements that we're putting on sponsors and researchers about transparency. That would be my feeling. But of course there's no hard evidence because we haven't done a survey to sort of find out whether that burden or, you know, perceived burden to meet research transparency requirements are deterring people from conducting trials.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane Germany (moderator) [01:03:06]

Thank you. I have a question from the audience here. I think that's also for Naho Yamasaki. If possible, can you go into further details about the personalized results of trials to participants? What level are you aiming for?

Nano Yamasaki, HRA [01:03:22]

We are not asking for any detailed level of information to be provided either to the Health Research Authority or stipulate in a guidance. But what we expect in this area in terms of the strategy, we have moved away very much from the sharing of research data and tissue, recognizing that there is quite a lot of work happening in this area already. So yeah, whilst we ask whether people have followed what they've declared to do in the application, we are not providing strict guidance in that particular field.

Matthias Perleth, HTA Verein [01:04:08]

I would like to come back to the trauma situation and why we are here. And thanks for Stefan [Sauerland], who has already solved the problem and provided us with a road map or a pathway how to move forward. And I think this is somehow compelling.

However, it's regrettable that the German regulatory agency, BfArM, is not represented today here. They are of course somehow in a situation which is very close to the Ministry of Health and political influence,

and so they are usually very careful not to do anything that is public. But of course, we would need to involve them in the reform as they probably could indeed easily transfer or translate mandatory registration into practice and do the monitoring.

As for the question of costs, often from Transparency International, why not starting on the European level? I think this is an interesting question, and I think there are probably two issues here. The first is it's probably faster to reach progress on a national level first, instead of waiting for something happen at the EU level. Second issue is that I'm not sure whether the European Commission or the European Union has the power to create requirements on a national level for interventions that are not regulated on an EU level. But I'm not a lawyer, so I'm only speculating here.

[Off-topic audience question omitted here]

Martin Smith, ex UK parliament [01:08:36]

In the UK experience, the nature of the statutory basis on which the relevant organization is set up is important… The thing that the committee found was that transparency was in the statutory routine for the HRA, that it had this responsibility for promoting this. And that was the key to express the despair of the committee saying, well, we think this is inexcusable. And the test, it has to be forward. And then that links to what you've been describing with BfArM and whether or not that is formally their responsibility and if it can be made their responsibility, seems to be a key question.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane Germany (moderator) [01:10:10]

Thank you very much. I have a question to the German panelists. What do you think about the current political will in Germany? Is the political will strong enough at the moment to start working on a clinical trial transparency system?

Christoph Stein, Transparency International Germany board member [01:10:35]

Yeah. Again, speaking as an active researcher. From my point of view, what I've experienced, the political will is there and we have just heard all the possibilities that were laid out very clearly. I think Germany would be ready to implement a lot of the same rules that were implemented in the UK.

Again, my question is why is the EU not sitting here? And my personal experience is we had a lot of dealings with the EU. We had to register. There is a big platform at the EU and it's pretty rigorous and it's working pretty well in my own experience. So I don't think really that Germany by itself can push all the other EU countries in doing the same thing, just like the UK hasn't been able to do that.

But I think we should definitely, in my opinion, we should definitely try to make a concerted effort and use some of the tools that already exist at the EU level and implement the whole system in the EU..

Daniel Strech, QUEST [01:12:13]

About the political will point. I mean, good to hear from someone who knows the politics in this regard that there is the assumption there is political will. I would argue that it probably should be the first practice oriented step, maybe from people who joined here together today, to check for the political will. It's unfortunately a very basic step that would be easier if you already had a German parliamentary committee that is addressing this. And we need to further consolidate this group.

To my knowledge, we currently don't have a political decision maker group that already have on the agenda this transparency issue. But if organizations, as they are represented here from Transparency International Germany over to Cochrane [Germany] and many others that are here together, if they do something together to get feedback from German policy decision makers about what is your political will, maybe relatively concrete guiding questions with regard to what we heard today, what would be necessary, outlining a little bit what in principle would be possible in Germany because we have certain resources available. I would recommend this could be an important next step to get. Feedback about the political will.

Including patient organizations. Very important point. So that there would be a certain interest voiced to the politics about can you please give us feedback on who is ready to maybe together with us work on something that at the end of the day might look a little bit like what is currently going on in the UK?

Stefan Sauerland, DnEBM [01:14:26]

I would also agree that if the time is not now, when then? We have a health minister who comes from a medical research background. He is a medical doctor. He has some experience in evidence based medicine. And most importantly, he now has some time after Corona is nearly over, hopefully to put on other duties. Probably a requirement that some stakeholders write a joint letter to the Ministry of Health and ask for an official statement directed to BfArM that they take over this role.

As to the question of whether it is better to engage university centers and use public engagement, I don't think that this is really working very well. If you have something legally binding that comes from an authoritative body in Germany, this always works better, I must say.

Martin Smith, ex UK parliament

So it won't surprise you that I very much agree with the point about establishing the political will. I think you can refer to the UK example in the sense of making very, very substantial progress here is achievable, which I think gives politicians hope that they can have an impact potentially within their own political cycle rather than something that would take ten years to come to fruition.

I would put aside a lot of the technical issues which are naturally front of our minds in terms of how do you define a publication and what about different kinds of trials that are approved in different ways? Just stick to the fundamental points about research waste and the accuracy of the research base. The duty that you have to trial participants to make use of their time and energy by publishing the results, and to make sure that what you're investigating can be taken forward in an accurate way. And just try and get free of the excuses for not making progress on this and demanding that there is a clear responsibility for making progress on this.

And then when it comes to the technical details, the technical experts working with the community can work those out. From the UK point of view, we were able to use the fact that UK Parliament has this strong parliamentary scrutiny process that can be very high profile. In fact, the chair of the Science and Technology Committee was a former government minister from a few years ago, former health minister, and so he had his own profile and he knew what could be achieved in terms of using scrutiny to try to shine a spotlight on a problem that needs fixing.

And so whatever the German equivalent of that is, say this shouldn't be allowed to continue, even if there are technical things to work out. I'm getting that ball rolling now. Seems like a very wise next step.

Naho Yamasaki, HRA [01:18:21]

I think, as Martin said, that political will is really important, as others commented as well. And some form of framework of enforcement, whether it's a legal means or other regulatory means through an agency that you have, would definitely help.

But I would really emphasize the kind of multipronged approach that is necessary as well. And I think in bringing the stakeholders together, many of whom already bought into this agenda and are driving forward that change, and as well about bringing in the patient voice. I think that was really crucial when we did the consultation of the strategy. We talked to many members of the public and I think what resonated with a lot of the people was that when people found out that these kinds of information weren't available or shared already, the results are not routinely shared with participants, people really were quite shocked. And I think we really need to move away from that state.

Matthias Perleth, HTA Verein [01:19:31]

I fully agree with what was just said. I think we should involve, for example, the important patient representatives. Some campaigns in the past have shown that patient representatives can become a very

powerful voice in Germany and can create public opinion and also to drive politicians to action, which I saw a couple of days ago in the case of Long Covid in Germany. And I think this can trigger some action.

I think it would probably not be enough to just write a letter to some decision makers. But I would take the letter issue as one piece of a more coordinated campaign that tries to try to employ a different strategy including, of course, letters to decision makers. But what we need is to set up some political opinion leader, ideally in the ministry, maybe the minister himself or any other high ranking personality, or a member of parliament. And in one of the committees of the German parliament, we have to set them on fire, I would say, in order to advocate for this issue.

And we should stress the advantages to setting up mandatory registration. And we probably should also stress that there is nothing bad about that. So there's no financial issues. Nobody can lose anything here. And I think this is important to keep in mind. It's not about distributing money or something like that. It's just about transparency. And there's nothing bad about that.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane Germany (moderator) [01:21:52]

I would like to read a question from the audience. I never understood why ethics committees do not check registration and publication. Is it a lack of resources? Is that the only limitation? Would anyone like to reply to this question?

Christoph Stein, Transparency International Germany board member [01:22:11]

Again from my own experience, ethics committees do not usually focus on this question. They are for some reason exclusively focused on the beginning of the study, on the burden for patients. And I have personally never been asked the question of publication, and I don't know why that is, but I think it should be. I totally agree. It should be part of their duties to think about publication, there's no question.

Maybe the rules need to be changed, the laws need to be changed, for ethics committees. That's one possibility. In Germany, this is not so easy because we have a lot of different ethics committees. We have ethics committees at the state level. We have 16 states in Germany. So each state has their own ethics committee and we have ethics committees at the institutional levels. So if you only take the university hospitals, we have about 36 university hospitals in in Germany. If you add that to the state ethics committees, that makes about 50 different ethics committees, and that doesn't even include the local ethics committees for community hospitals, for example.

So in Germany, it's always very difficult to come up with a general law that's binding for all the different institutions and the different states. But it should definitely be a law.

Daniel Strech, QUEST [01:24:10]

We would like to see all interventional trials to be registered according to the Declaration of Helsinki, but this is not really part of German law, Stefan. It's part of the physician position, soft law. So what could happen is that a physician loses his license to practice, but it's not really the stage we are at.

It's now ten years ago that I led a group for this umbrella organization of the German Research Ethics Committees [AKEK]. What would the 50 something research ethics committees in Germany think about study registration for all trials, not only the drug trials and maybe in the future, medical device trials? And you find this [AKEK] statement, this opinion piece from 2012 still on their website, which supports this in principle. The main argument at the end of the statement is that we as ethics committees in Germany, we don't have any legal back up for this. We cannot just require it. This is only for the drug trials.

When it comes to results reporting, it's more or less the same story. It's even a little bit more complicated because study registration in principle, you could require at the approval situation, as we have it for all drug trials. But to take results reporting into account during the ethics application, you would need at least to get feedback on whether completed trials published something or not, 12 months after completion date, for example, then going back to them. And then, you cannot refuse to approve the trial, but you can maybe try to give certain incentives to still publish results and so on. So the ethics committee is currently like a legal background beside the fact that they would also currently at least lack resources, personal financial resources to build themselves a process like this.

But like the UK initiative is showing, you can really centralize this, you can automate things and with one or two legal support mechanisms, you can then build this infrastructure. We will get everything registered automatically and at least you can send out automatically generated reminder letters 12 months after the study was completed. All of this, in principle, should not be something like rocket science. It would be possible in principle. But the ethics committees alone cannot implement this. They need to work together with some people who have political will and political decision power.

Valerie Labonte, Cochrane Germany (moderator) [01:27:13] I see that we are running out of time. Thank you, everyone, for a very lively discussion. I hope this meeting brought together the right people to initiate the process of creating a trial transparency system for Germany. Now I'm looking forward to seeing what will happen. Thank you, everyone, for your time today. It has been a real pleasure. Thank you.

[ENDS]

This transcript is published under a Creative Commons license (CC-BY 4.0)